The final Torah portion of Exodus, Vayakhel-Pekudei, concludes with the erecting of the Tabernacle.

The Torah states “And Moses erected the Tabernacle.” (Exodus 40:18) The fifteen verses that follow detail every aspect of the setup of the Tabernacle and everything it. What is striking about this lengthy description is the emphasis on Moses himself. The singular verbs clearly imply that this work was done entirely by Moses. For example:

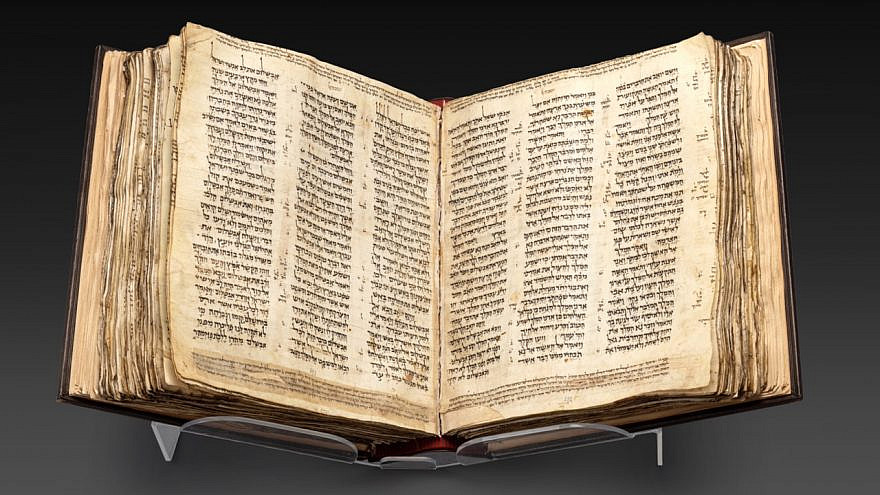

Moses erected the tabernacle, fastened its sockets, set up its boards, put in its bars, and erected its pillars. He spread out the tent over the tabernacle and put the covering of the tent over it from above, as the Lord had commanded Moses. He took the Testimony and put it into the ark, inserted the poles through the rings of the ark, and put the ark cover on top of the ark. – Exodus 40:18-20

On and on the text continues in this fashion, in the third person singular, for 15 verses. As if to emphasize that it was Moses alone who did all the work, the passage concludes with this verse:

He erected the courtyard around the Tabernacle and the altar, and he put up the screen of the gate of the courtyard; Moses concluded the labor. – Exodus 40:33

Whether Moses alone actually did all the work such as moving furniture and vessels, erecting the many large wooden beams, and building the courtyard, or he is being credited for the job because he was the leader is a speculative question worth pondering. For our purposes as readers of the Bible, we must ask a more basic question. Why? Why does the Torah emphasize Moses as the sole constructor of the Tabernacle? What lesson can we derive from this?

To answer this question, let’s explore another, more fundamental question regarding the Tabernacle. What was its purpose? Why was it set up just the way it was?

The great commentator and rabbinic leader Rabbi Moses Nachmanides (13th century France), known by the acronym Ramban, maintains that the Tabernacle, and the temple in Jerusalem after it, served as an extension of the revelatory experience of the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai.

As we read in Exodus 19, at Sinai the children of Israel surrounded the mountain. There were boundaries beyond which the people were forbidden to pass. There was an inner boundary into which only the priests were allowed and the point of contact with God was in the center. At that point of contact with God, the voice of God was heard and Moses was given the law in the form of the two tablets of the covenant. Moreover, as the Bible tells us, there was smoke rising from the mountain.

Similarly, with regard to the setup of the camp of Israel in the desert, the nation camped around the Tabernacle; there was an inner boundary for the Levites and priests. The people were not allowed into the inner part of the Tabernacle. At the innermost point of the Tabernacle was the Ark of the Covenant, containing the two tablets of the law given at Sinai. Atop the ark sat the Cherubs, the point of contact with God, the entry point of God’s prophetic word into the world. Finally, the burning of incense day and night produced a pillar of smoke that rose from the sanctuary, a few feet away from the Ark. Therefore, through the presence of the Tabernacle, the revelation at Sinai was experienced in perpetuity.

All of this can be equally applied to the temple in Jerusalem, which is geographically located in the center of the land of Israel, with the tribes of Israel surrounding it on all sides.

It is clear from this arrangement that the epicenter of the Tabernacle was the Ark of the Covenant. This was the only item in the innermost chamber, the Holy of Holies. Even the High Priest was only allowed to enter under only very limited circumstances. As mentioned, the Ark, situated in the Holy of Holies, contained the tablets.

Once again, the ark contained the tablets of the law and was covered by the Cherubs, which the Bible tells us was the entry point for God’s prophetic word. What does this mean? Simply put, it means that the covenant of the law represented by the tablets served as the basis for prophecy, the highest point of contact between God and man.

There is a powerful lesson here that we must understand. In the minds of many people of faith, the primary encounter with God is through prayer and worship. Prayer is certainly an essential component of our relationship with God. As Jews, we pray three times a day. When there was a Tabernacle or Temple, the primary form of worship was the sacrificial offerings. But notice the setup of the Tabernacle.

The sacrifices were offered in the outer area, not in the holy or holy of holies. In other words, the purpose of prayer and worship is to draw us closer to God. In fact, the Hebrew word for “sacrifice” korban, literally means, “that which draws close.” But our primary purpose and mission as servants of God is not prayer or the offering of sacrifices. Prayer and sacrifices, worship, is a means to an end. The most important way that we serve God is by carrying out His will on this earth.

Let me put this another way. When we pray to God, we are trying to get Him to do our will. When we study His word and obediently carry out His commands, we align our will with His. The purpose of sacrifices and worship is to draw us closer to Him so that we will ultimately embrace our mission, to serve Him by doing His work in the world. That mission is contained in the Torah, and in the prophetic word of God, represented by the Ark of the Covenant.

Moses was not the High Priest. It might have made more sense to us that if anyone should be putting the Tabernacle together all by himself, it should be Aaron, not Moses. But Moses was the greatest prophet and, more importantly, Moses was the one who relayed the Torah, God’s law and mission, to the children of Israel.

In many religious systems, the primary experience of relationship with God is prayer. In Judaism, it is Torah. Torah study brings a person to an understanding of the will of God. When one understands a particular verse or Torah idea, one is communing with God on the most intimate level. One is blending his thoughts with God’s thoughts, so to speak. In this experience, the will of God and our will become synonymous. It is a blending of our very identities with the Divine.

In prayer, I stand before God. In Torah study, I am with Him. More importantly, in fulfillment of the Torah, I become God’s agent, carrying out His will in the world.

To emphasize the primacy of Torah wisdom and practice as the most intimate connection to God, the Tabernacle – with the Torah at its center – was fully erected by Moses, the giver of the Torah.

As the Ramban compared the setup of Tabernacle in the camp to the revelation at Sinai, so too, this idea can be seen in the setup of the Jewish People in the land of Israel. Jerusalem, the epicenter of our encounter with God, sits in the middle of the country, while Jerusalem itself is surrounded by the camp of Israel.

Even as we turn towards Jerusalem in prayer, we must also open our minds and hearts to hear the message that is coming from Jerusalem. Ultimately, the surest way for God to dwell within our midst is through the study and practice of Torah.

“For from Tzion shall go forth Torah and the word of Hashem from Jerusalem.” – Isaiah 2:3

Rabbi Pesach Wolicki serves as Executive Director of Ohr Torah Stone’s Center for Jewish-Christian Understanding and Cooperation, and he is a cohost of the Shoulder to Shoulder podcast.